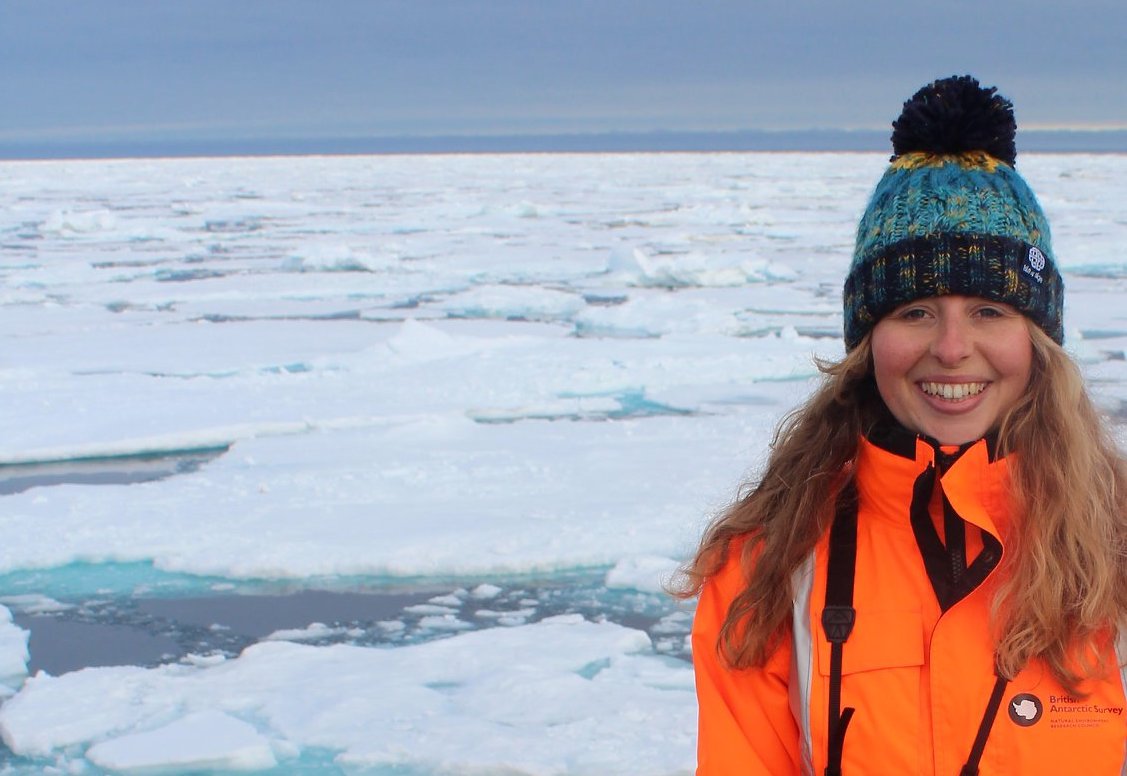

Marine Conservation and Changing Arctic Oceans – An Interview with Stephanie Sargeant

Often, when it comes to marine conservation, it’s the small organisms and important ocean systems that are overlooked. In this interview, marine biologist and conservationist Dr Stephanie Sargeant gives insight into the forgotten fundamentals of marine conservation, such as plankton and trace gases.

Steph is a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Sciences at the University of the West of England and her research is focused on marine microbial ecology, marine biogeochemistry and the application of environmental DNA (eDNA) for species management and conservation.

Why do you work in conservation and what inspired you to focus on marine conservation?

I really liked the big scale and how so many processes are interlinked together, it’s not just about one organism, it became about that organism respiring and those gases then in the water, those gases diffuse into the atmosphere, influencing our climate and that has a larger scale impact.

I think that, that kind of system science is what got me really interested. The marine environment is on such a large scale and that just blew my mind – looking at such small things but on a global scale.

Any impact humans have is going to unbalance that ecosystem and the services that are involved in it, so I think that was more my route into conservation. For me it’s more about conserving the whole system and the workings of the system, rather than being inspired by one particular organism.

What is the Changing Arctic Oceans Project?

In recent years there have been many profound changes in the physical environment, including natural and human caused events which have placed stress on Arctic ecosystems. It is unknown how the Arctic’s organisms, processes, gases and other ocean systems will respond to these changes. Ocean chemistry and oceanic processes are all interlinked and therefore they are the underlying foundations to any marine conservation.

The Changing Arctic Ocean Project was set up to address the uncertainties in the Arctic Ocean generated by climate change. It is the second largest research programme funded by Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Warming of the Arctic waters and ocean acidification alongside, increased light penetration due to ice-retreat and all have consequences for the production of trace gases (e.g. methane, nitrous oxide, carbon monoxide, and dimethyl sulphide) that influence the climate.

Part of the Changing Arctic Oceans Project is a programme called PETRA (Pathways and emissions of climate-relevant trace gases in a changing Arctic Ocean). This project aims to develop ecosystem models to identify the main controls on trace gas production in the future Arctic Ocean. This research is with the intention to answer questions such as ‘At what rate are these gases being produced in the surface of the Arctic Ocean now?’ And ‘Will the ocean-atmosphere exchange of these gases change over the next century?’

How did your participation in the PETRA project go? And what is it like to spend a significant amount of time at sea completing research?

Essentially, we did some incubation experiments, with a range of pH’s, predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, and a range of temperatures, ambient temperature and +2°C. We collected water samples from the pycnocline (the boundary separating two liquid layers of different densities) and looked at what happened to the gases but also to the microbes producing and using these gases to try and understand how those processes and the biogeochemistry of the water is going to change.

I personally love being at sea, it’s a very different environment. Essentially, you’re trapped on a ship with about 60-80 other people and you’ve got nowhere to go, but it’s a really nice community and fantastic experience. It’s great to have the opportunity to focus on your research 100% and not to be surrounded by life’s distractions. There’s also something very special about being out in the middle of the ocean surrounded by seawater and completely remote from civilisation.

Have you got any current or upcoming projects you are looking forward to?

I haven’t got any more time at sea planned at the moment, but we have got data back from the cruise I did before PETRA, called ZIPLOc (Zinc, Iron and Phosphorus co-Limitation in the Ocean) which was looking at trace metal co-limitation in the northern Atlantic.

We conducted some incubation experiments to look at what happens when there’s trace metal input from the Sahara into the northern Atlantic. We have just received some microarray data back which will hopefully tell us which genes plankton had switched on or switched off. This is known as gene regulation, which can also help an organism respond to its environment. We are going to try and analyse that dataset next so that will be exciting!

What are the best parts of working in conservation and science?

For me, in terms of being in academia, one of the best things is that you do get to do such a broad range of research projects and teaching, but I think really, it’s just the great people. In conservation you are surrounded by such fantastic people, most people are passionate about their job and feel they have a purpose which means they tend to go above and beyond, which is a really nice thing. And obviously hoping that we’re making some kind of difference in the world!

Are there any negative parts about your job?

I guess more generally in conservation science, the lack of funding is quite often an issue. In terms of academia, I really love the teaching and student aspect of it, and I wouldn’t change that. But, having so many responsibilities and ongoing projects can be quite stressful and time consuming. It is something to be aware of if you’re interested in pursuing that career path.

I think whenever you do a job that you love, it can take over everything which does mean trying to have a life outside of work becomes more challenging. But waking up to do a job you love every day is definitely a gift.

What key steps did you have to take to be where you are today?

I guess I had quite a direct route because I went straight from school to university, to do my undergraduate, then straight on to do my PhD because I couldn’t really afford to do a master’s.

I was lucky enough that just as I finished my PhD, my undergraduate supervisor was going on maternity leave and there was a short-term contract advertised to cover her teaching. As it turned out this experience was instrumental in leading me to my current role.

Taking such a direct route did mean that I didn’t end up doing any post-doctoral research after my PhD or take out any time to go travelling which is now harder given the level of responsibility I hold.

Do you have any advice for anyone wishing to work in conservation?

Remember that conservation is a broad field; it’s not just about the charismatic megafauna but about understanding the whole system, including gases in seawater and the microscopic algae that live on them.

Take the opportunities that come your way, even when they’re daunting. Try not to stress too much about the bigger picture because it will come together eventually. So far, everything has happened for a reason.

Want more? Why not explore Stephanie’s publications!

Careers Advice, Interviews, Senior Level, Ecologist, Educator, Scientist, Marine Conservation Jobs, Sustainability