Standing Tall for Giraffe Conservation | Part 1

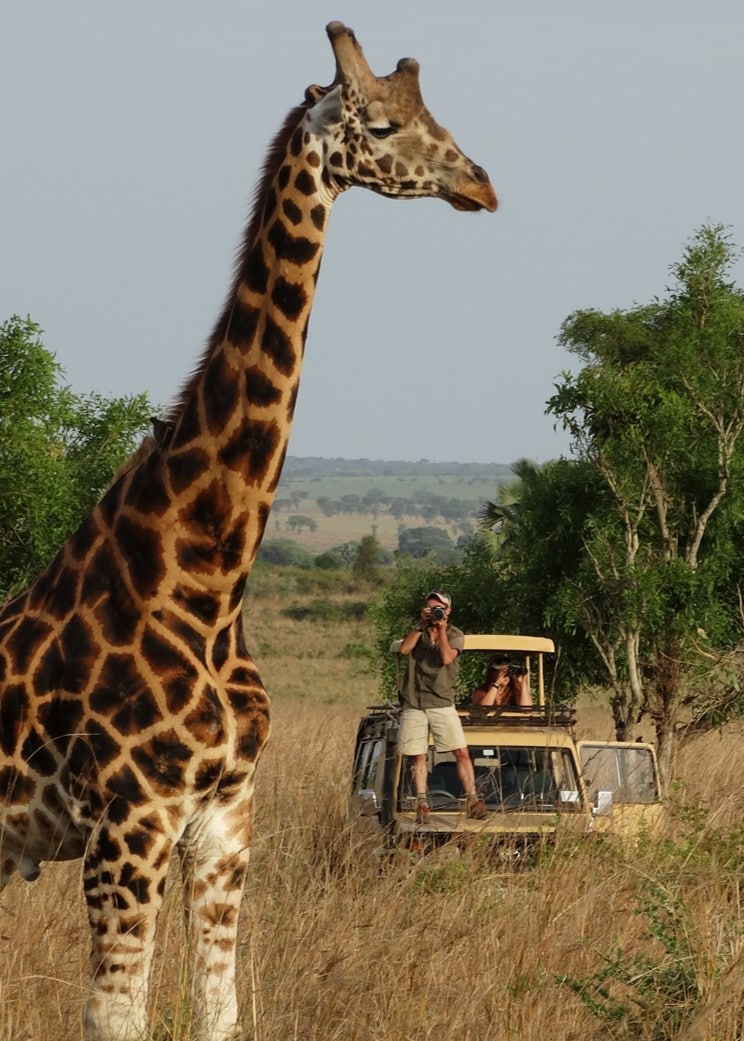

In this first instalment of interviews with the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, conservation ecologist Michael Butler Brown explores how science and diverse perspectives contribute to giraffe conservation.

The Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) is a globally operational organisation working towards saving giraffe in the wild. Using science to navigate conservation-based strategies and initiatives to best support wild giraffe populations. With a range of different conservation initiatives across Africa, the GCF supports project implementation, conservation monitoring, technical support and in the field “hands-on” conservation work.

One of the GCF’s species programmes is based in Uganda contributing towards the preservation of the Critically Endangered subspecies Nubian giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) and their habitat. Since 2013 the GCF and the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) have been actively working together in the field providing immediate conservation impact as well as ongoing research to reach longer-term conservation goals.

Michael Butler Brown is one of the key conservation ecologists working with the GCF and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute to aid wild giraffe conservation across Africa. In this interview Michael provides a detailed account about the role of science in applied conservation and the importance for diverse perspectives to implement and reach the long term goal for giraffe population survival.

Why did you decide to work in conservation?

At the risk of sounding overly saccharine, as a Conservation Ecologist I have the opportunity to study the interconnectedness of life and use that understanding to solve problems. I have always wanted to study animals in the wild – I’ve truly never wanted to pursue anything else – and I’m very fortunate to find myself in a position where I can work to understand and conserve these systems that I value. Conservation is an inherently dynamic and challenging field that requires diverse perspectives, eclectic skillsets, and creative approaches; as a result the practice of conservation ticks a lot of boxes for me personally. I get to use science to solve problems. This umbrella term of conservation provides a conduit for translating science into actions; it’s not only logically working through data and publishing findings, which in itself can have its own intellectual merit, but also using these understandings to in act positive change.

Moreover, working as a field ecologist, I get to operate under the sometimes challenging and always unpredictable field conditions, and I find the constant problem-solving in the bush and managing of logistics to be an incredibly fulfilling aspect of the job. These conservation conversations require not only rigorous science and understanding of ecosystems; but also an ability to understand and translate values across key stakeholders, local community members and government officials. Being able to creatively operate in these realms is a really engaging process.

What are your main activities in your current role?

My role is the Conservation Science Fellow for GCF and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. To give a broad overview of my position, I work to develop and implement science based solutions to giraffe conservation issues across Africa. On any given day you can find me doing a number of tasks in pursuit of that overall goal.

You might find me:

- Tracking giraffe in Eastern Uganda as part of a post translocation monitoring strategy

- Organising a conservation science symposium to bring together diverse perspectives to deepen our vision for giraffe conservation practices

- Working with partners across a growing network of researchers to figure out ways to modify surveying protocols and make our studies more comparable so we can scale up our inferences

- Working to address reviewer comments on the latest scientific manuscript

- Collaborating with government officials to draft strategies and policies to guide giraffe conservation initiatives.

- Or less glamorously under the hood of a land cruiser fidgeting with an uncooperative fuel pump

More recently during the lock down period I’ve been developing computer code to identify emergent patterns in giraffe movement data. These analyses will help us to understand new aspects of how giraffe interact with their environments.

One of our flagship initiatives is the Twiga Tracker Programme – a continental scale study of giraffe spatial ecology. With our various partners we are using GPS tracking units to remotely collect data on nearly 200 giraffe across eight different countries. Giraffe are a fascinating species covering a large area of sub-Saharan Africa ranging from; relatively mesic savannahs in Uganda to hyper arid deserts in Northern Namibia, semi-arid scrub land in Northern Kenya and everything in between. Trying to understand how giraffe interact with their environments in these incredibly diverse habitats can help us to understand some of the driving principles of giraffe movement ecology and space use so we can design and implement effective conservation strategies across their range.

What is the best part of your job?

Developing an intimate appreciation for the intricacy of these ecological systems and using that understanding to enact positive change. Working in beautiful places (I truly never feel more at home than out in the bush which is another added benefit) and working alongside great, dedicated and dynamic people.

It’s really not hard to stay motivated when you feel like you are working towards something you value.

What is the worse part of the job?

In conservation particularly the narratives are too often centred on loss and negative aspects of these situations. Conservation is sometimes framed as a “catastrophe driven discipline” in which you are constantly putting out fires and maybe in reality for some people that’s what it becomes. While it’s important to acknowledge the gravity of the problems and the urgent responses required, I think focusing on long term visions in routed optimism will counter some of that emotional burnout you might get from constantly focusing on negativity and loss.

Generally, I try to be an optimistic person because there are a number of powerful success stories. We can learn from those scenarios and be motivated by the successes as much as we can learn from the failures.

What are your career highlights?

Over the past six years we have worked with the Uganda Wildlife Authority to develop a country level giraffe conservation programme. With a long term vision directed by rigorous science we are seeing some remarkable trends in giraffe. The recent conservation narrative of giraffe in Uganda is a remarkably positive one. It seems like conservation done in the right way – starting with basic science and developing more robust baseline population estimates so that all subsequent decisions are made with the best available data. This process starts with developing an intimate understanding of giraffe ecology in particular systems and the unique threats they face so we can tailor strategies specifically to these systems. It’s also critical to hold stakeholder workshops to incorporate diverse perspectives and views including local knowledge and perspectives under these strategies. All of these efforts are dependent on establishing very sound and working relationships with local partners, and demonstrating commitment to build trust. We were also very careful to evaluate historical distribution and abundance trends so that the vision wasn’t taken in a miss guided direction by shifting baselines. Using this whole process we’ve been able to develop strategies and action plans including some very ambitious initiatives such as conservation translocations where we have been able to support the reintroduction of giraffe into some of their historical strongholds in Uganda.

When we started this programme back in 2014 there were essentially two populations of giraffe, now in Uganda there are five populations, all of which are increasing in size, which is incredibly encouraging. We are able to demonstrate the value of these initiatives with rigorous, science-based assessments, comparing key population metrics to reliable baselines. To go through that process and see the amount of work, investment and trust has been very rewarding, and sets a solid foundation for future initiatives.

What lessons have you learnt so far?

Effective conservation is routed in multi-disciplinary understandings across scales and having diverse perspectives in developing solutions. Being open to different ways of thinking, identifying a problem or conceiving a solution is instrumental in being able to move towards equitable solutions to conservation issues. In this way, it’s important to take advantage of every available learning opportunity to enhance your understanding of key issues or to develop skill sets necessary to address them.

What key steps have you taken in your career?

I think it’s important to realise that there is no one defined and accepted universal trajectory for conservation professionals. Everyone can make their own path to reach their own goals. Moreover, the realm of professional conservation practitioners is fortunately more diverse now than it has ever been, and some of the most innovative solutions are being drawn from incredibly diverse ways of thinking and doing.

For me personally, my professional trajectory was rooted in the scientific pursuits. Early in my career, I saw it as the best way to spend the most time in the field. With this goal, I found myself at a crossroads professionally. Leaving my undergraduate degree, although I committed to the idea of field ecology, I was on the fence about whether I wanted to do a more pure science route or the applied work. Throughout college and after I graduated, I worked a range of smaller contract field tech gigs, getting diverse perspectives on each of these positions and envisioning what possible career trajectories. This time was essential for me. It allowed me to see what I valued in the work and ultimately the application side of conservation was one of the most motivating factors; being able to turn results of these studies into meaningful actions is really where I derive a lot of my motivation.

I have worked my way through field tech positions and university affiliations as a way to stay engaged in the conservation community. My background is in science and ecology, trying to develop scientific studies to understand these ecosystems. I have gone through both a Bachelor’s degree in biology, a master’s degree in Conservation Biology. During this time, I also developed a much deeper appreciation for the organisational components, management, and finance associated with applied conservation. Although I’ve always identified as a field ecologist, I found these aspects of conservation to be essential for maximising impact and enacting meaningful change.

I then became the project manager for the Laikipia Zebra Project in Kenya, enabling me to hone all of these skills – designing and executing scientific studies, project management, bushcraft, and applied conservation – in a dynamic field environment. I eventually used this position to earn a PhD in Ecology, Evolution, Ecosystems and Society.

Pursuing a PhD is undoubtedly a substantial commitment, but it affords an unparalleled opportunity to think deeply about particular topics and systems for 5(ish) years and hone your craft. For me, working with GCF in Uganda, it also gave me the opportunity to directly apply the findings of these studies into meaningful conservation action in the field as I worked towards building the foundations of a productive conservation science programme.

What advice do you have for someone following a similar career path?

Try to be the type of person you’d want to work with. Some of these communities are small and tight-nit and your professional reputation is an important asset. As with any career trajectory, developing a professional network leads to productive collaborations and more opportunities.

Don’t be discouraged by failure! I know for me personally coming out of my bachelors degree and trying to get my first job in the field was challenging. Without hyperbole, I can say I was rejected over 100 times. Opening the first door is often the most challenging step and then once you start to develop that professional network things can snowball. Absolutely make the most of every opportunity presented to you and work tenaciously when you get it.

Perhaps a more practical bit of advice for field conservation is to develop marketable skill sets. People come into (especially early stage career) positions with a bachelors degrees, ambition, enthusiasm and passion – which are all great attributes – but it’s also useful to develop skills that can set you apart and can make you an asset in the field.

For example if you want to manage a field project and you’re going to be constantly working with vehicles in the bush it would be useful to develop some sort of vehicle repair skill set. If you can do a quick fix on a land rover in the bush you can save a trip to the mechanic and essentially save the project the equivalent of your monthly pay check and justify the cost for putting you out there in the field in the first place. Some of the conditions can be challenging to work in so it is good to have skills and experiences that demonstrate you are a prudent investment.

What are your next steps?

Well truly there is no shortage of work to be done in my current capacity and I am really looking forward to building on this solid foundation and scaling up some of the inferences of these studies. There is a lot of potential to learn a lot about giraffe and have a big impact on giraffe conservation across their range. That is where I am focusing most of my efforts at the moment.

It’s great having the opportunity to work in science and application and have the ability to creatively use all these networks and opportunities.

Want more? In Part 2 of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) interviews, Veterinarian Sara Ferguson provides an in-depth account of the day-today threats faced by giraffe in Murchison National Park, Uganda.