How a literature degree prepared me for a career in conservation

Claire Adler came to Synchronicity Earth with a lifelong interest in conservation, a lot of anxiety about climate change – and a degree in medieval English literature.

Claire shares how studying our past, from peat bogs to the origins of colonialism, taught her the skills and perspectives she needed to start her career in conservation.

This story was originally published on Synchronicity Earth’s blog.

When I explain my background to my coworkers, I tend to emphasise that my research approached medieval literature from an environmental perspective. I’m interested in the new stories old texts can tell us about humanity’s place in the natural world.

But in reality, I didn’t spend much of my degree focused on the environment: I was too busy learning how to decode medieval handwriting, gaining a grounding in the history of the period, and spending lots and lots of time reading very weird poems very, very carefully.

These pursuits, for me, are fascinating, enriching, and endlessly exciting—but I did occasionally wonder how I could justify spending time on them, while earth is in the midst of the greatest catastrophe in human history. Perhaps not the best time for poring over fifteenth century manuscripts.

A background in the humanities

A few months ago, my manager shared her rationale for hiring me. I was cheered, and somewhat surprised, to learn that most of these reasons can be traced to the skills I developed as a literature student. In my “ability for critical thinking in communications (e.g., is this source problematic?)” I recognised countless hours spent weighing up various articles on medieval maps. In my “strong passion for editing,” I saw the ghost of essays saved from disaster by the judicious application of the red pen. Even my “good understanding of the type of working patterns which work for [me]” derived from learning to organise my own time while writing my master’s dissertation.

I felt so included at Synchronicity Earth that my team successfully convinced me to try rock climbing. Image © Nina Seale.

Since coming on at Synchronicity Earth, those skills have made me feel like a valuable member of the team, despite having far less conservation expertise than most of my coworkers.

“Of course, writing experience comes in handy for blog posts and social media captions, but it also makes it easier to effectively structure a presentation, to consider the ethical implications of the language we use, and to envision ways of talking about the biodiversity crisis that inspire action, rather than despair.”

For me, environmental despair arrives hand-in-hand with a feeling of resentment and injustice—it seems desperately unfair to have been born into the worst crisis in human history. Beyond the practical skills it has afforded me, I am grateful for my humanities background because it enables me to place today’s crisis in historical context. Recognising the long European legacy of violence against the living world reframes the present moment as an opportunity to finally create a radically new society.

Peat and oil: repeating history

In The Edge of the World, the historian Michael Pye traces the origins of the modern, money-based economy to the shores of the “low countries”. There, traders began accumulating wealth by trading commodities for currency, rather than land. At the same time, they started destroying the land they were on—the industry that powered this new trade economy was powered by burning peat.

Peat is plant matter that accumulates in bogs, where the lack of oxygen prevents it from fully decomposing. Forming layers up to five meters thick, it can be mined, dried, and then burned like a less-powerful coal. Although technically renewable, peat is very slow growing. A layer three metres thick takes around 3,000 years to form.

Today, peat is mined for sale as fertiliser, despite growing opposition to the destructive and carbon-intensive practice. Image CC nz_willowherb.

Large-scale peat mining took off in Flanders (in the north of modern-day Belgium) in the 1100s. From there, it spread across the region, moving from one urban centre to another as local supplies were depleted. By the end of the fifteenth century, all easily-accessible reserves were gone.

In response to this early energy crisis, peat-reliant industry did not transition to alternate forms of fuel. Instead, much like today’s fossil fuel industry, it pivoted to increasingly environmentally costly forms of extraction. Novel technology made it possible to gather peat found below sea level. These stores came at a price—without the bogs working as natural dykes, sea water came rushing in. Soon, between 115 and 230 hectares of land was surrendered to the ocean every year. Ultimately, peat mining below sea level flooded a staggering ten per cent of Holland and Utrecht.

“Unsustainable energy consumption provoking environmental crisis (complete with rising sea levels!) is, of course, uncomfortably familiar. But the phenomenon is not just an uncanny parallel of today’s climate crisis. It is part of the same story.”

Those peat-burning industrialists released unprecedented quantities of carbon into the atmosphere. Although negligible in today’s turns, it’s now busy warming the planet, along with all the fuel we’ve burned since.

The consequences of colonialism

More importantly, we still live in their world. The drivers of colonialism were complicated, but unsustainable European economies depleting their local resources was almost certainly one of them. Indeed, while the Dutch depleted their peat, England was in the midst of widespread panic about timber shortages—panic soothed by tales of vast forests in the so-called ‘New World’. England, like Belgium, the Netherlands, and many other European states, went on to found a brutal colonial empire, rooted in the idea that land exists to be exploited, and that anything, and anyone, can be ‘extracted’, bought, and sold.

Today’s economy still operates according to this same paradigm. The wealth of the Global North can be traced directly to colonialism and slavery, and avenues for accumulating new wealth often replicate similar dynamics. One need look no further than the Inga 3 dam proposal. Long pushed by foreign investors, the massive hydropower project would provide energy for mining and export, at immense cost to the ecosystems and local communities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, one of the poorest countries in the world.

Why is the Democratic Republic of the Congo so poor? Well, largely because it was subjected to nearly a century of brutal colonisation, carried out by the descendants of those same peat-burning Belgians.

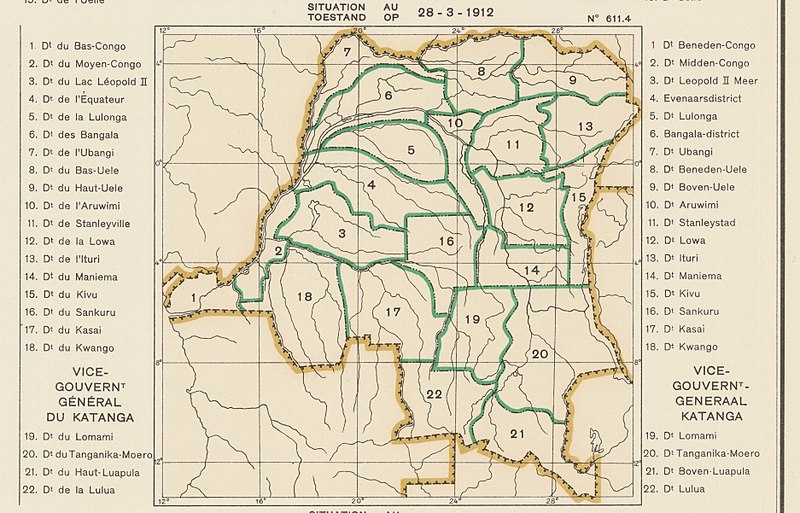

This map records district divisions in the Belgian Congo as of 1912. The relative brutality of colonisation between regions can still be traced in contemporary Congolese demographics.

From this perspective, the twenty-first century ecological crisis stops feeling unlucky, and starts looking inevitable. It should come as no surprise that building a different world, one that values people over profit, ecosystems rather than resources, sufficiency rather than excess—in short, a world that would leave the peat in the ground—is a slow and often frustrating process.

The living world needs new stories

At Synchronicity Earth, I have had the privilege to be a very small part of this process. Many of our partners engage in locally-led conservation and restoration work, work that implicitly resists the dominant capitalist narrative by casting care for the living world as intrinsically worthwhile. Others challenge the contemporary economic order more directly, from pushing back against Inga 3, to fighting for the recognition of communal, Indigenous land rights based on stewardship rather than ownership.

This fall, I’m moving on to pursue a PhD in medieval and early modern literature. As I envision my future as an academic, I know it will be profoundly shaped by my time at Synchronicity Earth.

Of course, I’m excited to one day advise my students on how their literature degree could translate into a career in conservation. I will be able to confidently say that no one needs to choose between biodiversity and storytelling: the living world needs new stories.

Our stories need the living world

But perhaps more importantly, I leave Synchronicity Earth more convinced than ever that our stories need the living world. When we look at history through the lens of today’s environmental crisis, different things stand out.

This late fifteenth-century Dutch illustration of the creation of Adam and Eve emphasises the beauty of the natural world, despite widespread environmental destruction at the time. Image: Public domain.

In a conventional history of Europe, the peat bogs of Northern Europe are a footnote in the invention of a modern economy. Were it not for my own grief and anger about contemporary climate change, I suspect I would find them interesting, but unimportant. As it is, I can’t imagine the Middle Ages without them. If I was telling the story of our time, that is where it would begin.

Had I told that story before arriving at Synchronicity Earth, I would have been tempted to end in the same vein. I would have written about the fossil fuel economy, the worsening impacts of extractivism, and wealthy societies that continue to prioritise the accumulation of capital over all else, even as greed literally devours the land beneath our feet.

Now, I know all this is true, with consequences and mechanisms far broader than I realised. But I also know we are in the first few years of a global push for peat restoration, from English moors to Malaysian swamps. For those early industrialists, the idea of growing peat only to leave it in the ground would likely have been incomprehensible. It is my good fortune to live in a time when such projects are possible—and my responsibility to work on their behalf, in all that I do.