Conservation Photojournalism and It’s Important for the Future of Conservation

I recently met Neil Aldridge under unforeseen circumstances, but the passion, the drive and the commitment that pours out of Neil when he talks about conservation issues is inspirational.

Neil spent much of his early career volunteering and working with conservation organisations such as The Wildlife Trust, The Galapagos Conservation Trust and Natural England. However he spent a fair bit of time on a reserve in South Africa gaining his FGASA qualification (Field Guides Association of Southern Africa), and also holds a Masters degree in photojournalism from the University of the Arts London.

Sometimes as scientists, we can be a little inept at being able to communicate our findings or put simply, we find it hard to make them seem sexy. The way in which we campaign conservation issues has an enormous impact on the outcome for the species and habitats involved.

What Neil does is tremendously important for the future of conservation; in an age where Instagram is over taking Twitter as people want something quick and visual, conservation photojournalism is the stronghold of a campaigns success.

What is Conservation Photojournalism?

As a concept, I would define it as the creation of photographs and photo stories that benefit conservation by challenging perceptions, increasing understanding, inspiring action and unlocking funding.

Do you remember your very first camera?

I’ve had a camera for as long as I can remember. Photography has been in my family for generations and so it’s always just been part of my life. What unlocked my excitement and ambitions was my first SLR camera – a Pentax MZ-50 – that my father gave to me as a teenager. Finally, with a 300mm lens mounted on the front I was able to capture shots of the wildlife around me in South Africa. I began comparing my pictures to the work of professionals that I was seeing in magazines and books and started to look at where I was going wrong.

Which milestones in your career do you think helped you to get where you are now?

Committing early in my career to a big self-generated project like the story of the African wild dog helped to show editors that I was committed to capturing stories and prepared to work hard to get the necessary shots. This helped pave the way for being asked to carry out future commissions.

Doing a Masters degree in Photojournalism also helped to focus me and cement in my mind the kind of photography I wanted to be doing. Importantly, it got me away from hanging out with pure wildlife photographers and allowed me to learn from documentary photographers working in other genres.

Finally, I would say winning European Wildlife Photographer of the Year in 2014 was quite a considerable milestone and turning point, but in an unexpected way. You would think securing a major competition win like that would lead to all kinds of good things but it mainly made me re-assess my work and actively cut back on a lot of unnecessary activity. The win helped me to see the real nature of many people and the industry, and I’ve had a productive 18 months of real clarity since.

Do you think it’s important to have a unique concept behind your art when entering photographic competitions?

It certainly helps to know what has been successful in a competition before when you’re planning your entries, but not because you should try to copy it. The jury is looking for something they haven’t seen before. But before you get to competition stage it’s helpful to approach your photography with the aim of capturing something in a new way. So firstly, learn to be comfortable with the idea that a picture may not be everyone’s cup of tea. My ‘Living Rock Art’ image was something different and it captured the imagination of judges in international competitions, but equally it failed to get past the first round in others and it got a lot of negative attention in the press.

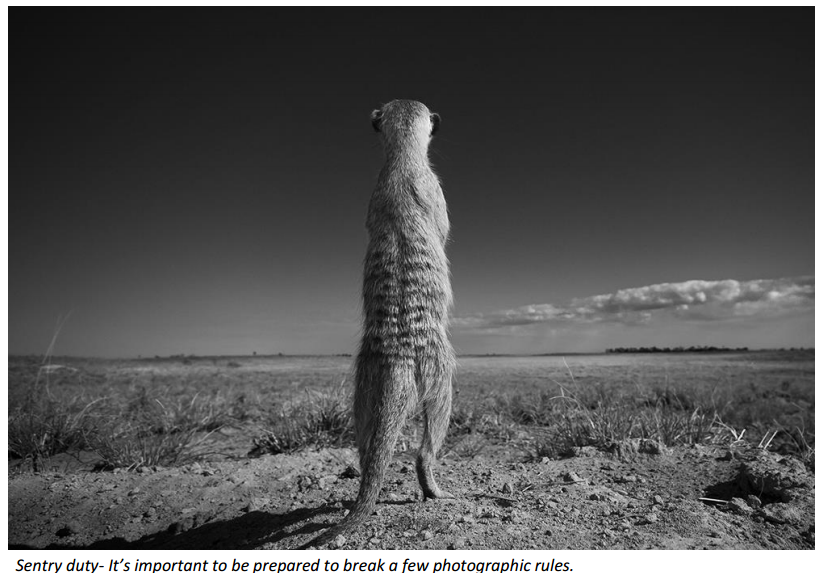

Secondly, be prepared to break a few photographic rules. My black and white photograph of a meerkat called ‘Sentry Duty’ had the meerkat dead-centre and the subject had its back to me. Again, a lot of people hated it because it didn’t conform to a few basic rules of photography. But, importantly, a lot of people that matter really liked these two pictures, which brings me to my final point – have a few useful colleagues who you can ask for their opinion on certain images. Photographers tend to look at images differently to your gran, who will always tell you how talented you are no matter how bad a picture is!

What current projects do you have going on at the minute?

I’m currently working on two projects. The first is a self-generated project on the red fox and its relationship with people in Britain. I find this a fascinating and utterly bizarre topic. There are so many elements of the story to cover because people interact with this species in such a broad spectrum of ways. In contrast to my fox work, the rhino project is a collaboration and while it does involve developing stories, it’s also about creating engaging content to help promote the work of the conservationists I’m working with. And I strongly believe this is important for rhinos right now. There are just some causes which need people to bring their skills together and create synergy.

Your book ‘Underdogs’ focuses on the IUCN Endangered African Wild Dogs. What compelled you to create a book about this particular species?

I often ask myself the same question. On paper, it made little business sense committing myself to flying half way around the world to tell the story of a species few people outside of Africa really knew or cared about when I had zero track record as a photographer. What’s more, I had only ever seen wild dogs once in the wild before I started the project. But I had a plan and I was committed to telling the story of this remarkable species. In fact it was their relative anonymity outside of Africa that inspired me and so I targeted the international audience with the book more than South African bookshops.

I should say that despite having only seen them once in the wild, I had been fascinated about wild dogs for years. I researched their story and conservation issues as part of my professional wildlife guide training in 2005, and it was then that I realised the importance of this as a photographic story. They’re incredible animals and remain my favourite species by a long way. Nothing quite compares to sitting at a den when the pups come above ground and are welcomed by the pack.

Have you ever felt insignificant at any point in your career? Many people may be deterred early on due to the competitiveness and popularity of wildlife photography. What advice would you give to these people?

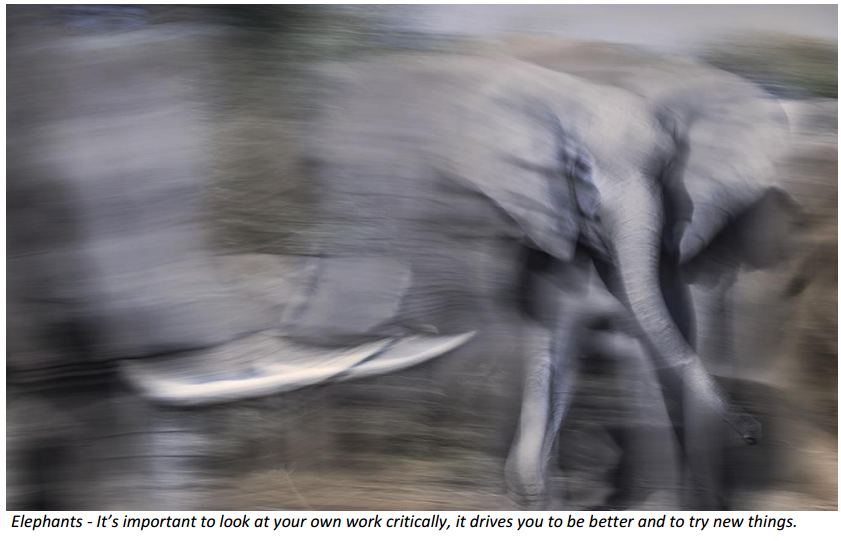

I constantly feel insignificant. I actually think it’s a healthy thing. I constantly feel my work could be better and I draw inspiration from other photographers who are creating work that I respect and wish I had in my own portfolio. I really feel you need to be able to look at your own work both constructively and critically and know where you could improve. It certainly drives me to be better, to try new things and be more creative.

So my advice for anyone starting out in photography is to have a plan and stick to it, be clear on your values, be patient and never stop feeling like you could learn more or improve your work in some way. If you’re in it for the glory and money, maybe grow your hair and buy yourself an electric guitar because it takes discipline and patience to make an honest living out of creating photographs that matter and that can make a difference.

I’ve heard you offer portfolio and tuition advice? Could you tell us a bit about the service?

Together, Sophie my partner and I, offer a unique perspective for photographers looking to improve their work and take their photography to the next level. We review portfolios and offer advice based on what the photographer is looking for, and we are careful to keep our fees flexible and accessible for photographic students. Between us, thanks to our respective experience and skills, we advise on the aesthetic elements of images, technical aspects, ethics, equipment choices, subject matter, career development, competition entries and publishing options.

Finally, what would you say are the three most important things to remember when taking a photograph of a wild animal?

First and foremost, always put your subject first. Not only can judges and editors pick up tell-tale signs, such as body language, that animals are stressed, but your behaviour as a photographer may influence how that animal interacts with people in the future. Secondly, try and conceive of a shot in your head before going out to capture it.

We will always have unplanned opportunities when photographing nature, which is what keeps photography exciting, but planning and story boarding a shot will help you see potential angles, backgrounds and elements in the frame that you may otherwise miss if you just leave things to chance.

Finally, take the best picture you can in-camera and reduce the need to make amends afterwards during post-processing. Having to try and make a picture useable by pushing levels to the limits in post-processing will always impact on the quality and usability of a photograph.

Neil Aldridge is an award-winning photojournalist, writer and professional wildlife guide. You can see more of his work on his website: conservationphotojournalism.com