Saving the Elephants in Laos

The Elephant Conservation Centre (ECC) does incredible work preserving the Laotian elephant population in the wild and under human care. The ECC in Laos currently have 32 elephants, and with a range of different conservation initiatives including education and reproduction, the ECC is working hard to save them.

In this interview, ECC’s biologist, Anabel Lopez Perez, talks about their work combatting increasing pressure from deforestation and poaching that currently threaten elephants in Laos PDR. Read on to learn how she got into this field of work, her thoughts on elephant tourism and how you can get involved.

Credit: Paul Wager.

Why do you work in conservation and what is your current role at the ECC?

Work in conservation is very needed, and we need to preserve the little wildlife we have left. We have to put a lot of energy into doing this before it is too late. It is an emergency to do this work and I like doing it.

My role at ECC has changed over the past seven years, but I now work in management and research. I manage the breeding programme together with the mahouts (a person who works with and tends an elephant) and then I produce research to better understand the social and physiological needs of captive elephants so we can provide better management for them.

Credit: Paul Wager.

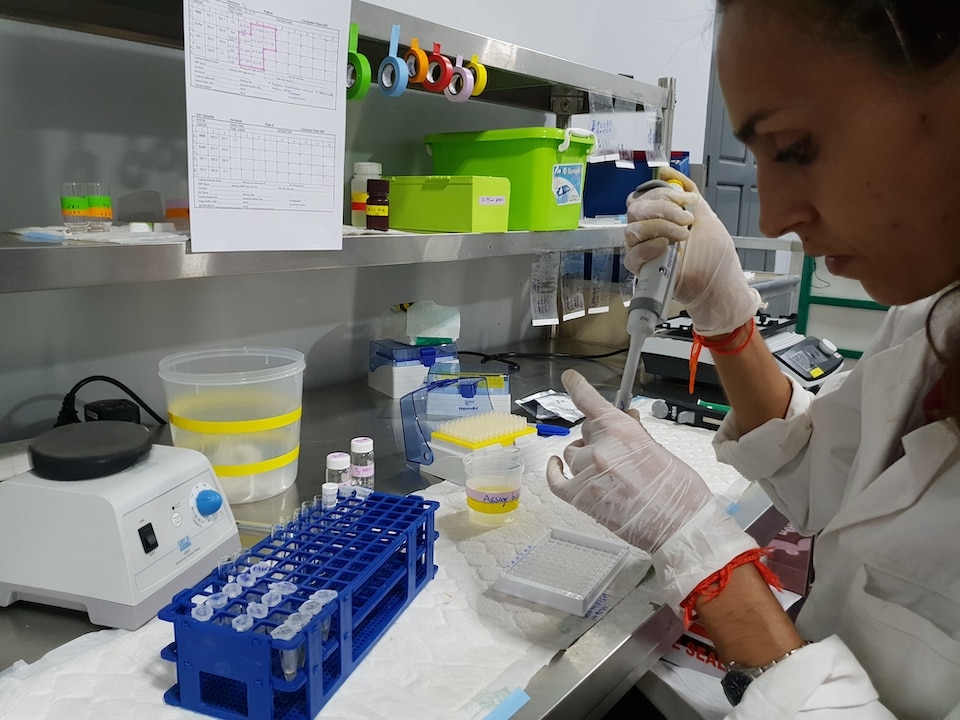

It is a combination of laboratory work and behavioural psychology. Half of the work is in the forest observing the behaviour of the elephants and collecting faecal and blood samples.

The other job is to then analyse the blood and faecal samples in the lab. It is a combination of laboratory and practical work, to try to target what factors (management, health, etc) can trigger physiological and behavioural changes in the captive elephant population.

How did you get in contact with the ECC in Laos?

When I finished university, I travelled through Laos and volunteered at ECC for a week, then extended my volunteering for a month. I then left, but they said it was very busy and they called me back. So I went back and then I just never left really!

Credit: Paul Wager.

I was always fascinated by wildlife and this is a job that I always wanted to do and something I expected to have when I started studying biology. You never think it is a possibility until it arrives by accident – I came first as a volunteer, but it was more like a great experience for me rather than a job!

This kind of job is rarely advertised on websites – go and volunteer and meet people. If I needed to bring a new biologist in, I would first find someone through volunteering as it can be hard, and you don’t want to hire someone for a year who might not make it two weeks! This kind of job is hard to find. All my friends who work with wildlife started first as a volunteer in their current job.

What is the best part of your job?

All of the parts are amazing but observing the elephants in the field is my favourite part more than anything else – just to observe them and later investigate it all in the lab to see if what we observe is right or why they behave in that way.

Credit: Paul Wager.

It is good to see them in a natural environment. It is good to observe the elephants and help them with a better life by reading their behaviours.

Are there any bad parts of the job?

Not really! Probably working in extreme weather conditions like forty-degree heat or heavy rain where you have to cancel everything. The weather is very extreme in Laos, but I love hot weather so it is not a big problem! The worst part is being so exposed in the forest to all these weather changes.

What are your career highlights so far?

I am really happy with providing more social time to the elephants and to be leading this through the elephant management. To manage them properly to give them more social time with other elephants is important.

Credit: Paul Wager.

We are proud of the social aspect in elephant management but also our new laboratory – this is a good step forward because it is a useful tool for breeding, and is the only laboratory is Laos. It is very new – we established it last year in 2019. We should be very proud as thanks to the labs we can do better research.

Before it was difficult as we didn’t have proper tools or equipment to do comprehensive research. But now we have amazing mahouts and the lab so we can move forward and do something better. I think this is probably our biggest achievement.

We also released five elephants last year in Nam Pouy National Protected Area – this is also a big achievement. We selected five elephants for a soft release and can now use how they behave in the wild for our research.

The elephants are free in the protected area but they are still under our care. The mahouts go out every few days and track where they are using GPS. So far they are doing very well, and they even socialise with wild male elephants, so who knows, we may have some new pregnancy thanks to these encounters! We don’t know when the next herd will be released but we are working on it.

Deforestation is a big problem, so we all need to start to be more conscious and be more sustainable with our daily actions since releasing and/or protecting elephants. It is not only the responsibility of people in Asia, but the responsibility of everybody.

Do you have any problems with poaching, logging or trekking camps in Laos?

Poaching elephants is not the biggest problem in Laos. Deforestation and destruction of habitats is the bigger problem that we are most concerned about right now. If we continue to destroy their habitat it will be very difficult for them to survive in the wild.

Also, they are megaherbivores and they eat around two hundred kilograms of food per day. If elephants don’t have a healthy forest, there is a higher chance in the future that they start to raid crops, putting the locals and the elephants at risk.

Credit: Paul Wager.

We have many different actions that we do to help resolve this – one is education in schools. Last year we planted 1000 trees with the government and schools on our land.

In the national park we had to focus more on patrols and see what we can do to solve the problem and the issues between human activities and wildlife.

What are your thoughts on elephant tourism?

The tourist industry can be very confusing as nobody really knows what is right or wrong for the elephants. The difficulty with some tourism businesses is that they can focus on abusive strategies where the biggest interest is not the elephant’s welfare, but money.

Credit: Paul Wager.

The welfare of the elephants depends on the management of the place. If it is well managed and the money goes towards conservation practices or to provide a fair living condition for the elephants under their care, then this is positive.

Things that you should be aware of in tourist camps are:

- How the elephants are handled.

- How many hours the elephants have to rest.

- How many hours they have to socialise with other elephants.

- Access to natural food and water.

- The length of chain and for how many hours they are chained during the day.

- What kind of equipment and how it is used to handle the elephants.

- Level of mahout expertise.

- How much time per day they spend interacting with tourists.

At ECC we are working on introducing science-based guidelines and proper certificates for tourism camps to protect and conserve the elephants.

We are part of the Asian Elephant Captive Working Group (AEWCG) in order to provide advice and guidance based on science to those who are awarded certificates. It involves many camps around Asia that now have standard guidelines and targets to enable positive elephant tourism experiences for both humans and elephants.

Do the mahouts have to go through training to look after the elephants?

They do, but traditionally there is no mahout school. They learn with their families. Normally being a mahout is a traditional job, so your father is a mahout and teaches you how to look after the elephants. You learn by going with other mahouts in the forest and experiencing what to do. The tradition is becoming lost, but you still need to be trained by an experienced mahout to show you how to take care of the elephants.

During this training mahouts learn what areas are safe or not for the elephants in the forest, what the elephants eat and need, their behaviour, what the symptoms of a sick elephant are and how to handle a male or female elephant.

The mahouts at the centre do go through regular workshops with experts to learn more about welfare, in addition to their traditional handling skills.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to follow in your footsteps?

You should be very passionate and if you really want to try then you can’t expect somebody to come to your door and offer you a job. For me, living in Spain, I would not be working in Laos unless I had gone out there. You have to be very open minded in looking at different options.

Credit: Paul Wager.

When you have a passion and like the work you do you have to follow your heart. People who work in conservation tend to be passionate and really like their job – in some roles you may need to work for free initially and sometimes people don’t work in conservation because many job positions are non-paid at first. It can be demotivating to start at voluntary level but is definitely worth it!

Be creative and show how you are valuable in projects and how you can improve it. Don’t give up and if you really want to work in something then go for it. Even if it doesn’t work out you end up with an experience that is always there in your life. The longer you stay somewhere the more you are likely to find chances.

Want more? Learn more about the ECC’s work in Laos on their website or make a small contribution to a jumbo cause! If you’re also interested in African elephants, you can find out what it’s like keeping elephants alive in South Afica.