On the frontlines of human-elephant conflict with Robin Cook, Elephants Alive

Growing up as a young boy in South Africa, aspiring to be a game ranger, Robin Cook is now contributing to a cause that is bigger than he ever imagined. Working with the most charismatic animals of the world such as elephants, is a dream come true for many conservationists and for Robin it all became a reality when he started working with Elephants Alive! Elephants Alive is an organisation based in Hoedspruit, a town situated just outside of the Kruger National Park. They work to ensure the survival of elephants and their habitats and to promote harmonious co-existence between man and elephants. As a recent graduate, Robin talks about his experiences in research and conservation that have led him to work with one of Africa’s Big Five animals and he offers advice for anyone that wishes to follow in his footsteps.

What is your current role and the key tasks associated with that role?

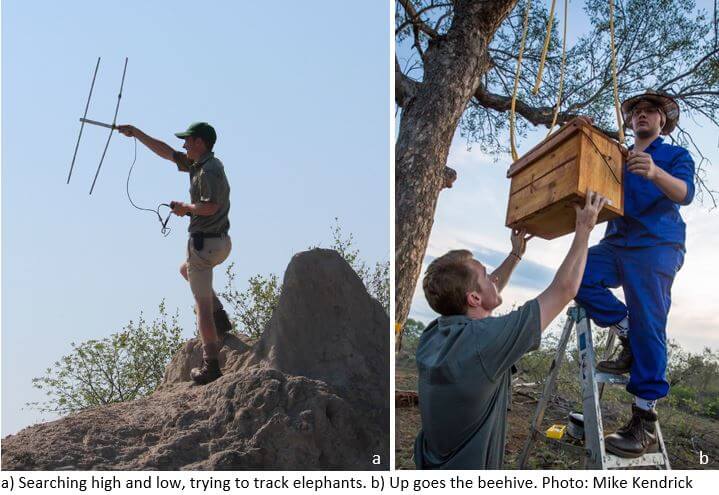

I am a researcher at Elephants Alive working with human-elephant conflict under Dr. Michelle Henley, Co-founder and Director of the organisation. My job is to find mitigation methods to overcome human-elephant conflict in the form of elephants destroying properties, breaking out of reserves and breaking down trees. I look at the impact elephants have on trees and the repercussions of those behaviours on the surrounding ecosystem. This involves looking at seed and seedling predation from rodents and herbivores that affect tree demographics. Looking at the ecological perspective allows me to analyse the situation at different levels and find appropriate mitigation methods. I also work on the elephant-bee project, which looks at using beehives hung from trees as a means of deterring elephants.

What’s the best and worst part of the job?

Spending the bulk of my time outdoors and doing what I love is probably one of the best things about the job. I also get a chance to do something that matters, from the smallest analysis work to the big projects. Being a part of the system at all levels allows me to learn about various projects and get involved in them. I feel like there is always room for me to grow. The African bush is always fantastic for camping and many landowners will invite us to stay on their premises. Being able to do things that the normal public would not do is definitely very exciting. The only downfall of the job is being away from my family, friends and my two Jack Russell dogs. My life has always been in the city so I do miss home from time to time. However, I do get the opportunity to meet amazing people that come to work at Elephants Alive and being in the bush is so serene that I don’t miss the hustle and bustle of city life.

All suited up and ready to put up beehives

What has been a career highlight for you?

There are always many exciting moments but one event definitely stands out. I was fortunate enough to have been part of a collaring operation to collar my favourite elephant named ‘Proud’. It was such an amazing experience to be able to touch his tusks and be able to collar him. He was the very first elephant that I tracked by myself after learning how to use the telemetry equipment, the first elephant whose dung I collected and the first one I had a close-up encounter with whilst he was feeding. They say you never forget your first which is probably why he is my favourite.

Another exciting moment was when we hung 50 beehives on trees in the middle of the night. I had never imagined I would be walking through the Kruger National Park in the middle of the night in a bee suit, hanging hives. It was quite an exhilarating experience.

What made you choose conservation and what key steps have you taken to get to where you are?

Getting my MSc in ecology, environment and conservation has provided me with a good foundation to move forward in conservation. As a young boy I went on many trips to the African bush which inspired me to be a game ranger. As I grew older I wanted to be a wildlife vet and save animals but it wasn’t until I watched a documentary with the term ‘zoologist’ being mentioned that I knew research in wildlife would be a great path. I knew I needed a degree and after I understood what a zoologist actually does, it allowed me to explore my options in conservation. Along the way I ensured I was networking and making connections with people in the industry, which led me to my role at Elephants Alive.

Safe guarding the trees from bark-stripping using chicken-mesh Photo: Moritz Muschic

Specific to your work with human-elephant conflict, what advice would you give to someone about working with people and wildlife?

It is crucial to take a step back from the wildlife side of conservation and look at the social aspects too. During my post-grad, I was fortunate to have done a course on ethno-ecology which allowed me to understand the social aspects in conservation. We visited rural areas close to the Kruger National Park and it was a big eye-opener for me to see the families living next to a reserve that had their crops raided by wildlife and the individuals working to feed their family that were negatively affected by other wildlife in the area.

After my MSc, I had the most incredible experience in Sri Lanka working with human-elephant conflict. I worked as a project co-ordinator on the Elephants and Bees Project’s Sri Lankan study site and it was the first time I saw farmers having their rice patties completely destroyed by elephants in a single night. What would have been their food and income for the next few months was all gone in one night. I had to work with other researchers to find solutions that would help the farmers without harming the elephants. I stopped seeing things from a western conservationists’ point of view and started looking at the whole system.

These experiences allowed me to realise that it was not about the preservation of saving wildlife but about working with people in poverty stricken areas to create harmony between humans and wildlife. Poverty is likely to stay for the foreseeable future and the best way to move forward in conservation is to consider social factors when making decisions about wildlife.

Do you believe there are significant measures in place to deal with human-elephant conflict?

South African human-elephant conflict is very different to the rest of Africa because in South Africa we fence off our elephants. Our biggest concerns are the loss of trees, breaking of fences and encounters with villagers. Ivory poaching has only just started to infiltrate the Kruger National Park in the northern sector and it is still a relatively new thing. In a country like Kenya, they are trying different methods to deter elephants from crops such as using beehives, using chillies around crops and planting buffer crops which elephants don’t eat. Elephants will then avoid those areas and human-elephant conflict is reduced. While there are many mitigation methods in place, we certainly need to explore new solutions when dealing with an ever-expanding human population and ever-shrinking elephant habitat.

What advice would you give someone wishing to follow in your footsteps?

Getting a degree will help you to understand key concepts of ecology and conservation but you should also focus on doing courses relevant to your interest. Networking is key whether it be through courses, workshops or conferences. It will really help you get into your industry and also make a point of emailing people to ensure that they know who you are.

That I find is the most helpful to get your foot in the conservation door and it allows you to get a sense of the industry as well as the role you can play in it. Volunteer and do internships because it allows you to gain that field experience. A career in conservation is not always as glamourous as it sounds. There is lots of field work but just as much deskwork to be done. Interning and volunteering allows you to get a sense of whether working in conservation is or isn’t for you.

About the Author

Hiral Naik is an MSc distinction graduate in Ecology, Environment and Conservation from the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. Growing up in Africa, she spent much of a time outdoors, in the wilderness and became passionate about nature and wildlife conservation. Hiral wrote her thesis on the evolutionary ecology of diet in snakes and herpetology (reptiles and amphibians) is largely where her interests lie. Hiral’s other passion is travel which led her to work as a research assistant for two months in Peru in 2017. She also works as a research developer and education mentor for Wild Serve, an NPO focusing on urban biodiversity conservation. Her life’s goal is to travel around the world to create harmony between wildlife and humans in conservation and play the role of ‘captain planet’. When she isn’t sitting behind a computer working for conservation, she can be found scuba-diving, doing photography or having fun on some epic adventure. She hopes to combine her passions and communicate the importance of conservation and sustainable development through environmental journalism, environmental education and as a Conservation Careers Blogger. Hiral runs her own blog hiralnaik.wordpress.com.